Cardiology Case #15

Primary Author: Dr Alastair Robertson; Co-Authors: Dr Hywel James and David Law

Background:

A 70yo female presented to ED with several weeks of intermittent chest pain and SOB, followed by the pain becoming more constant over the last few hours. She had a background of peripheral vascular disease and hypertension, and was a current smoker.

Observations were Sats 96% on air, HR 80, BP 150/80, temp 36.6.

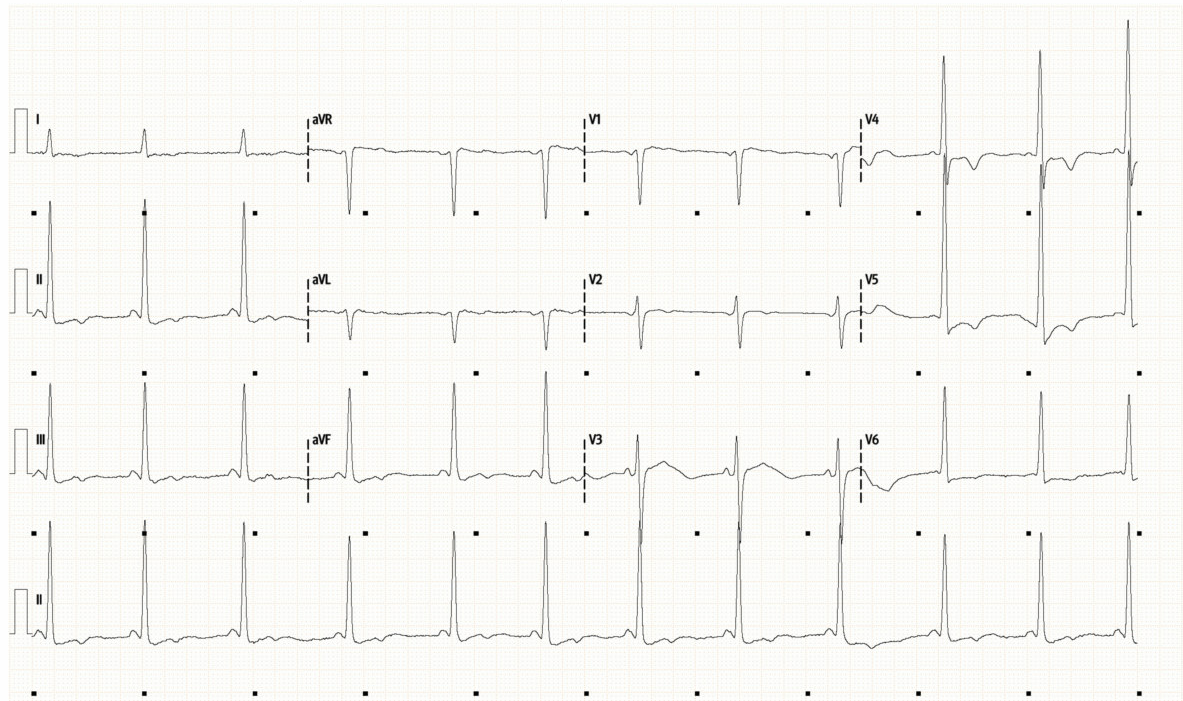

CXR and ECG are shown below.

-

ECG shows sinus rhythm with a rate of around 80. The QRS is narrow with normal axis.

Of note are large QRS voltages suggesting LVH. There is unusual ST depression and obvious T wave inversion particularly in the lateral leads V4-6.

This is an abnormal ECG which could be due to ischaemia, but raises the possibility of structural heart disease.

Chest XR shows hyper expansion in keeping with smoking, and some non-specific bilateral lower zone infiltrates but lungs are otherwise clear. Heart size appears normal.

Cardiac POCUS:

The two clips below are a modified or ‘low’ parasternal long-axis which is a view part-way between a Parasternal Long-Axis and an Apical Long-Axis.

What is your first impression?

Basic POCUS:

Immediately one can appreciate that the LV does not look normal.

The apex appears thickened and hypertrophied. In the bottom clip you can also see both papillary muscles connecting (via the chordae) to the mitral valve leaflets.

The thickening appears to start around the mid-cavity and involve the apex. The LV wall thickness and architecture at the LV base (just distal to the mitral valve) looks fairly normal.

This is Apical Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (Apical HCM)

Focus on: Apical HCM

Apical HCM (often called “Yamaguchi Type”) is a variant of HCM, where the hypertrophy is confined to the LV apex. This creates its characteristic “Ace of Spades” appearance on echo or angiography.

This is in contrast to the more common ‘Classic’ or ‘Asymmetric septal’ HCM which often involves the LV outflow tract and can cause obstruction of this (hence often being termed HOCM or Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy).

Apical HCM does not usually cause LVOTO, and is more common in Asian populations.

Typical Findings in Apical HCM:

Microvascular dysfunction may cause chest pain or angina symptoms.

Impaired diastolic filling may present as dyspnoea.

ECG classically shows ‘giant inverted T waves’ in precordial leads V2-V6

There may also be inferior and lateral T-wave changes

Echo Findings in Apical HCM:

The characeteristic ‘Ace of Spades’ appearance of the LV apex may be seen.

Apical hypertrophy (defined as wall thickness >1.5cm although this can be indexed to BSA)

A normal (or near-normal) wall thickness at the LV base (<1.0cm). As such an apical wall thickness to basal wall thickness ratio of >1.5x is sometimes used as a criteria.

Obliteration of the apical cavity during systole is seen.

Apical Aneurysm - a thinned akinetic or dyskinetic pouch at the true apex - is one of the most important features to identify due to the high risk of significant complications.

Common Complications of Apical HCM

Apical Aneurysm formation is a complication which can then lead to:

Apical thrombus and systemic embolism

A focus for arrhythmia - particularly VT and/or Sudden Cardiac Death

Cardiac Failure due to progressive diastolic dysfunction from hypertrophy

Other Arrhythmia e.g. atrial fibrillation

As mentioned earlier, the risk of LV Outflow Tract Obstruction is far lower in Apical HCM compared to ‘Classic HCM’ and the risks mainly centre around apical aneurysm formation causing thrombus or malignant arrhythmia.

Diagnosis is typically via a combination of echocardiography, angiography, and cardiac MRI (which shows late gadolinium enhancement [LGE] of the LV apex due to microvascular dysfunction).

Intermediate POCUS

When assessing a patient with Apical HCM the main complication of concern is apical aneurysm.

Firstly put colour over the LV apex. In the top video below you can see that during systole there is high velocity flow leaving the hypertrophied apical region (seen as a narrow strip of light blue flow). This is reassuring as it indicates there is dynamic flow in this region not suggestive of aneurysm or stasis.

Secondly carefully assess the apex for aneurysm. Good apical views are important and fan slowly through the apex. The bottom clip is an apical 2-chamber view showing a different perspective on the LV apex.

Case Conclusion:

The patient remained haemodynamically stable, but had a mild hs troponin rise peaking at around 60ng/L. BNP was elevated at 4000ng/L. She was treated initially as a NSTEMI.

She underwent coronary angiography which showed mild diffuse coronary artery disease with no culprit lesion - for conservative management.

She did not have an apical aneurysm.

She likely had some anginal pain from microvascular dysfunction and an element of diastolic dysfunction secondary to previously undiagnosed Apical HCM, compounded by other vascular risk factors.

She was discharged on aspirin, a statin, and an SGLT2 inhibitor with planned cardiology follow-up for ongoing surveillance of her cardiomyopathy, and to consider familial screening of first-degree relatives.

Finally: management principles for Apical HCM

Medical Therapy:

Is broadly similar to management of diastolic heart failure

Beta-blockers or CCBs can decrease myocardial workload

Volume optimisation and consideration of e.g. SGLT2 inhibitors.

Anticoagulation:

Is required for LV thrombus or presence of atrial fibrillation

Is also strongly considered in the setting of apical aneurysm in the absence of thrombus.

ICD insertion:

In the presence of high-risk features for malignant arrhythmia (apical aneurysm, documented VT/VF, unexplained syncope, FHx of SCD)

Septal Reduction Therapy (SRT):

Can be performed either percutaneously or surgically, however is rarely required for Apical HCM due to the far lower likelihood of LVOTO.

Genetic Screening:

Screening and counselling of relatives, in particular first-degree relatives.