Cardiology Case #16

Primary Author: Dr Alastair Robertson; Co-Authors: Dr Hywel James and David Law

Background:

A 60 year old female presents to ED with a 2 week history of progressive breathlessness - now even on minimal exertion - and intermittent palpitations.

On examination she has pitting oedema to her thighs and decreased AE in both lung bases. Her pulse is fast and irregular.

Her observations are RR 24, Sats 92% on air, HR 190, BP 103/60, temp 37.3.

Her ECG and CXR are shown below - what is your impression?

-

ECG shows an irregular narrow-complex tachycardia with a rate of around 190bpm. As it is irregular this is atrial fibrillation rather than SVT.

The axis is normal. There is widespread ST depression, particularly in the infero-lateral leads which likely represents rate-related ischaemia.

CXR is notable for a moderate to large right sided pleural effusion, and a small left sided effusion. There is no obvious mediastinal shift.

This patient appears to be in failure secondary to AF with RVR with signs of shock and haemodynamic instability.

What would your initial approach to rate control be, and why?

Will cardiac POCUS help make a decision?

Cardiac POCUS:

Ultrasound here can be crucial to assess cardiac function to help guide management given the concern for cardiac failure. Beta-blockers are often the first-line agents employed in the setting of rapid AF, but in the setting of severe LV impairment can precipitate cardiovascular collapse.

Have a look at the clips below

TOP: a ‘modified’ parasternal long-axis. Due to patient anatomy this is a low window, and not a true long-axis but closer to an off-axis 4-chamber.

MIDDLE: a parasternal short axis

BOTTOM: a subcostal 4-chamber view

Basic POCUS:

The top clip, whilst not a proper long-axis clearly shows that the LV is moderately dilated, with rapid rate and very poor systolic function. Given the known bilateral pleural effusions it is important to exclude pericardial effusion and tamponade. There is no significant pericardial effusion here.

The short-axis clip is at the level of the LV mid-cavity. The LV function is very poor globally, with no region of the LV contracting effectively. Between this and the top clip we can qualitatively estimate the EF as being severely impaired with an EF ~ 10-15% (any EF <30% is severe impairment). It is worth noting that LV function can often appear poor when in AF with rapid ventricular response due to poor diastolic filling and compensatory high heart rate, however this patient is clearly in severe cardiac failure.

The subcostal view confirms poor LV function, but also shows a dilated right ventricle, with poor systolic function. The Right Ventricle (top of picture in subcostal) should appear around two thirds the size of the LV whereas here it is dilated (larger than the right ventricle). This shows that the patient is in bi-ventricular failure, with LV failure causing elevated pulmonary pressures and consequent RV failure.

When one sees a dilated and/or failing right ventricle, then consider the common causes such as pulmonary hypertension, RV myocardial infarction, & Large PE.

Intermediate POCUS:

Mitral Valve Assessment

We have established that this patient is in severe bi-ventricular failure.

Further important assessment includes assessing pulmonary pressures, as well as gauging for mitral regurgitation function.

The top clip is our modified long-axis (same view as the top clip above) with colour doppler over the mitral valve. We see a modest MR jet, which is posteriorly directed into the posterior wall. In a normal heart this would most likely be classified as ‘mild’ or ‘mild-moderate’ MR.

However and importantly, this patient has a very low cardiac output and is in a ‘low-flow state’, with an LV that is unable to generate significant pressures. In this setting it is easy to underestimate mitral regurgitation. Given the low-flow state this jet represents moderate to severe functional MR (‘functional’ refers to MR due to failure causing dilation of the LV at the mitral annulus, rather than an intrinsic problem with the valve leaflets).

Intermediate POCUS - Pulmonary Pressures:

To measure pulmonary pressures remember that we need to first measure the systolic pressures in the Right Ventricle by using the tricuspid regurgitation.

Use colour doppler to identify the best TR jet you can find. This is best done from an apical 4-chamber view. If you slide the probe more medial you will distort the RV shape, but will often get a good TR jet for measuring pressures.

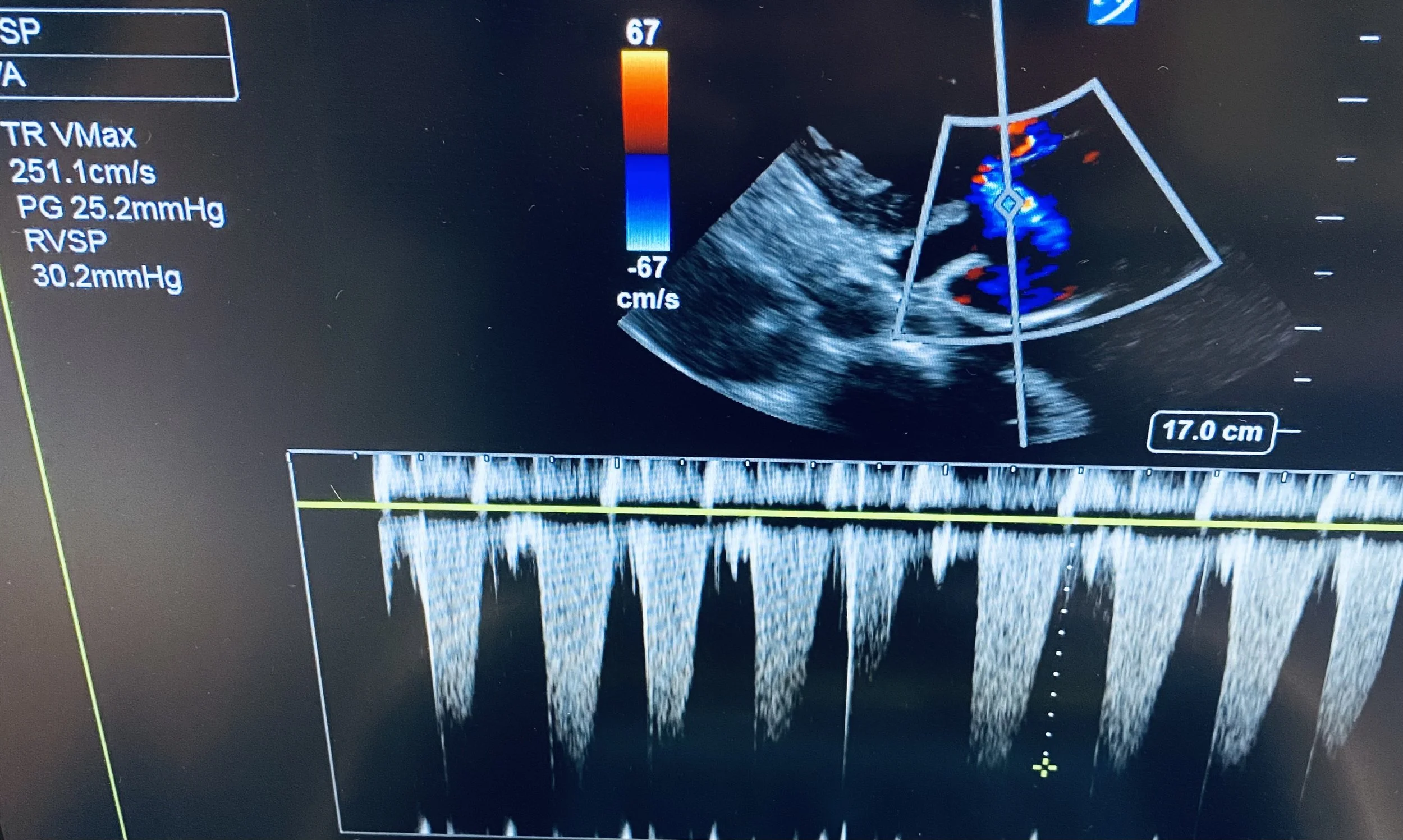

Place CW doppler through the TR to obtain a parabolic TR jet as seen in the still above.

Most ultrasound machines will have an option for ‘TR Vmax’ - use this to mark the bottom of the parabola and the RVSP will be calculated automatically.

In the top picture the TR Vmax was 251cm/s which corresponds to an RVSP of 30.2mmHg

In atrial fibrillation there will be beat to beat variation, so it is important to either take several measurements, or to pick a representative ‘average’ beat.

The bottom clip shows an IVC view. Here the IVC was dilated at >2.1cm and with less than 50% respiratory variation. The right atrial pressure (RAP) was therefore estimated at 12-15mmHg. Pulmonary Artery Systolic Pressure (PASP) was therefore (uppermost) estimated at 15 + 30 = 45mmHg.

Normal pulmonary pressures are below 40mmHg. Pressures in the range of 40-50mmHg would usually indicate mild pulmonary hypertension. However, as with mitral regurgitation, pressures must be assessed in context of cardiac output. Given the severe RV impairment the RV than cannot generate significant pressures. A PASP of 45mmHg thus signifies significant pulmonary hypertension in this setting.

Also, note the smoke-like effect in the IVC, this is Spontaneous Echo Contrast (SEC) which indicates stasis of blood due to the low-flow state.

Review Case #12 for more detail on pulmonary pressures.

Case Progress:

Initial management was electrolyte replacement followed by a rate-control straregy for her rapid atrial fibrillation.

The patient was initiated on an Amiodarone infusion as well has being loaded with oral Digoxin.

She remained haemodynamically stable so cautious diuresis with IV furosemide was started.

Thyroid function tests subsequently returned with an undetectable TSH (<0.01mI/L)

Free T4 was elevated at 62 pmol/L (normal range is 12-22)

BNP was 1,500

Is this patient in thyroid storm?

Thyrotoxicosis & Thyroid Storm:

Thyrotoxicosis and thyroid storm are a clinical spectrum, with thyroid storm being a life-threatening emergency. Features of thyroid storm can include hyperthermia, hyperglycaemia, delerium, tachycardia, high-output cardiac failure, hepatic failure, rhabdomyolysis and ultimately multi-organ failure.

Thyroid Storm does not have rigid diagnostic criteria, but the Burch Criteria can be helpful in suggesting if thyroid storm is truly present.

Causes of thyroid storm include:

Graves Disease

Toxic Adenoma

Toxic multi nodular goitre

Autoimmune thyroiditis

Usually associated with some kind of trigger such as: infection, iodine load (e.g. contrast), drugs (e.g. amiodarone, thyroxine), physiological stress (e.g. MI, DKA, surgery, trauma), or pregnancy/labour.

This patient had developed thyrotoxic rapid atrial fibrillation which had progressed to severe high-output cardiac failure (a phenomenon where high cardiac output - driven by e.g. sympathomimetics, thyrotoxicosis, or high metabolic demand - eventually cause failure of the ventricles, progressing to a ‘low output’ state.

Whether she was in true thyroid storm in unclear; using the Burch Criteria she scored >50 points which is “highly suggestive of thyroid storm”.

Principles of Management:

In this case, management revolved around addressing her two main issues which at times were competing:

1) Severe Bi-Ventricular high-output failure:

This is managed as for other causes of cardiac failure

Control of AF (either rate or rhythm control)

DCCV for unstable arrhythmia

If stable, agents such as Amiodarone or Digoxin are preferred initially

Support ventilation

NIV for respiratory distress, after load reduction (e.g. GTN) in the setting of hypertensive crisis/SCAPE

Consider draining large pleural effusions or tense ascites to ease ventilatory burden

Optimise fluid status - this requires diuresis as long as haemodynamics will allow

IV furosemide often first-line agent

Inotropic supports for decompensated frank cardiogenic shock

Consider Adrenaline, Dobutamine, Milrinone, Noradrenaline

Mechanical supports (ECMO, IABP for refractory shock)

Consider anticoagulation if EF <30% (risk of LV thrombus) or in new AF

Medium term management may include cautious beta-blocker use, diuretics, and SGLT2 inhibitors

2) Thyroid Storm:

Can be a true ED emergency requiring aggressive intervention.

Aggressive cooling if hyperthermia present with non-invasive, and invasive methods.

Intubation & paralysis may be required for hyperthermia or agitation.

Target a temperature of <40 C

Consider regular paracetamol but avoid NSAIDs

Steroids - IV Hydrocortisone 200mg, then 100mg Q6h

steroids inhibit the peripheral conversion of T4 to T3

However, consideration needed as may worsen fluid retention/oedema

Thyroid suppressing agents either Propylthiouracil (PTU), or Carbimazole

PTU is the preferred agent, and is safe in pregnancy, but there can be issues in concurrent hepatic failure/cirrhosis (which is not uncommon). Dose is 1g load PO/NG, then 250mg Q6h

Carbimazole is safe in liver failure, but cannot be used in pregnancy. Dosing is 20mg PO/NG Q6h.

Iodine

Give Lugol’s Iodine 8 drops PO 1 hour after giving PTU or Carbimazole

This blocks further thyroid hormone production via the Wolff-Chaikoff Effect

Cardiac Stabilisation - beta-blockers are usually used to help control tachycardia associated with thyroid storm

There is a very real risk of beta-blockers causing cardiovascular collapse in acute high-output failure so must be used cautiously!

Echo first!

Propranolol is useful as it also inhibits peripheral T4 to T3 conversion.

Esmolol is sometimes considered safer as due to its short half-life it can be quickly ceased if cardiogenic shock occurs

Metoprolol is another potential option.

Manage Atrial Fibrillation

DCCV is rarely effective in thyroid storm, due to persistent trigger

Amiodarone, Digoxin, or beta-blockers are all options in the short term

It may be that AF must be tolerated whilst hormonal control is achieved

Avoid further thyrotoxic insults

Treat precipitating cause e.g. sepsis, MI, DKA

Avoid loads of iodinated IV contrast where possible

Avoid medications such as Amiodarone where practical

Case Conclusion:

As is often the case, by the time the diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis was made the patient had already had a loading dose of IV Amiodarone, as well as IV contrast with a CTPA.

Given her severe AF-related biventricular failure a decision was made to prioritise rate control to avoid further decompensation. An amiodacrone infusion was continued, as well as oral digoxin. Beta-blockers were avoided in the acute phase due to risk of precipitating cardiogenic shock.

Cardiology, Endocrinology, and ICU were all involved in her ongoing management.

The patient was given steroids and PTU for thyroid suppression, and IV furosemide to initiate diuresis.

Her heart rate improved to around 130-150bpm on admission to CCU, but she remained in AF for some days before eventually reverting back to sinus rhythm. Metoprolol was initiated as her ejection fraction began to improve on the ward.

She was successfully discharged home with cardiology and endocrinology follow-up.

Spaced Repetition - Pulmonary Pressures

Key Points:

Gold Standard is Right heart catheterisation with a mean arterial pressure of >25mmHg signifying pulmonary hypertension (PHN)

Echo estimates right-sided systolic pressures, with pressures >40mmHg being elevated (this roughly corresponds to a MAP >25mmHg).

PASP 40-50mmHg is mild PHN, 50-65mmHg is moderate PHN, and >65mmHg is severe PHN.

PASP = RAP + RVSP

RVSP is the pressure difference between the RA and the RV in systole

RVSP is measured by putting CW doppler through the tricuspid regurgitation jet to calculate the TR Vmax.

RAP is estimated from the size and collapsibility of the IVC and is usually between 3 and 15mmHg

Tips:

The best doppler alignment with the TR jet is usually from an A4C view, but is sometimes found more medially, or even from a parasternal window.

IVC measurements may be unreliable if the patient is on PEEP (NIV or intubated) and will also vary with hydration status.

In atrial fibrillation there will be beat-to-beat variation so use a ‘representative’ beat, or take >/= 3 measurements and average them.