Cardiology Case #17

Primary Author: Dr Alastair Robertson; Co-Authors: Dr Hywel James and David Law

Background:

A 32 year old male presents to ED with several days of generalised lethargy and breathlessness. He is noted to be tachycardic with an irregular rhythm.

He has no previous PMHx, non-smoker, no drug use.

RR 18. Sats 96% on air. HR 130. BP 120/80. Temp 36.8.

-

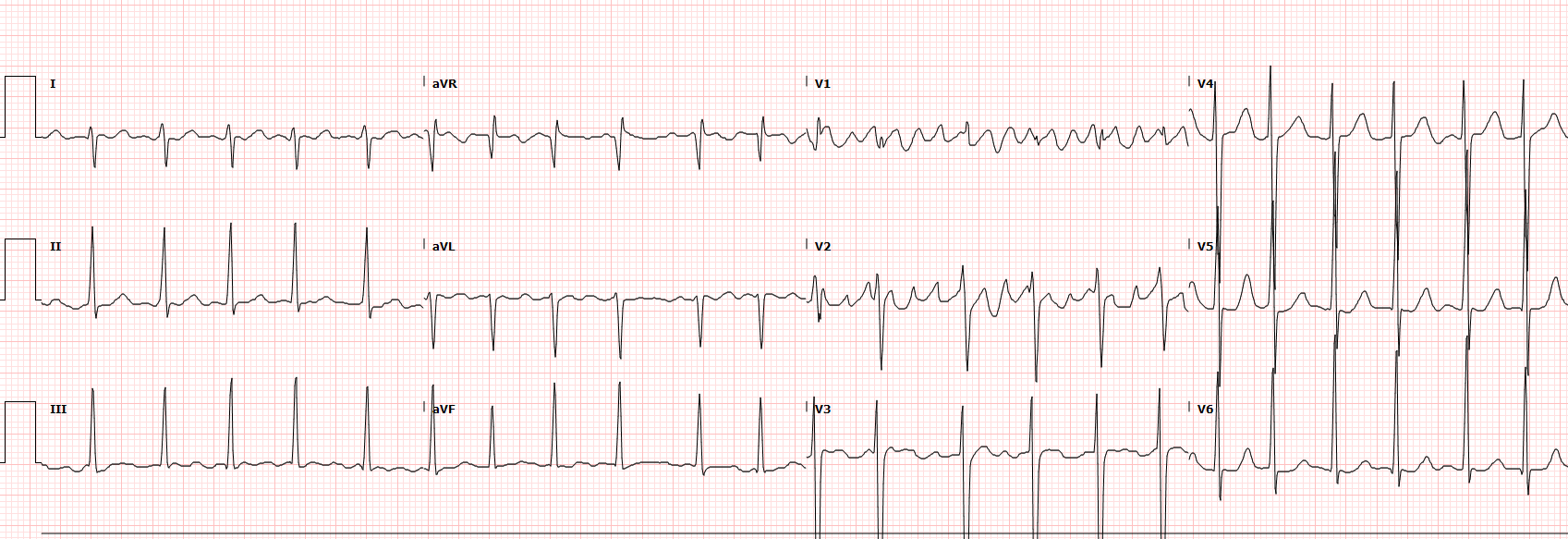

ECG shows a narrow-complex tachycardia with a rate of around 140/min. It is largely regular, with some variation which favours atrial flutter with a variable block. There were some ECGs for this patient that were suggestive of Atrial Fibrillation.

Flutter waves are visible in leads V1 and V2.

There is right axis deviation and a prominent R wave in lead aVR suggesting an element of Right Ventricular strain.

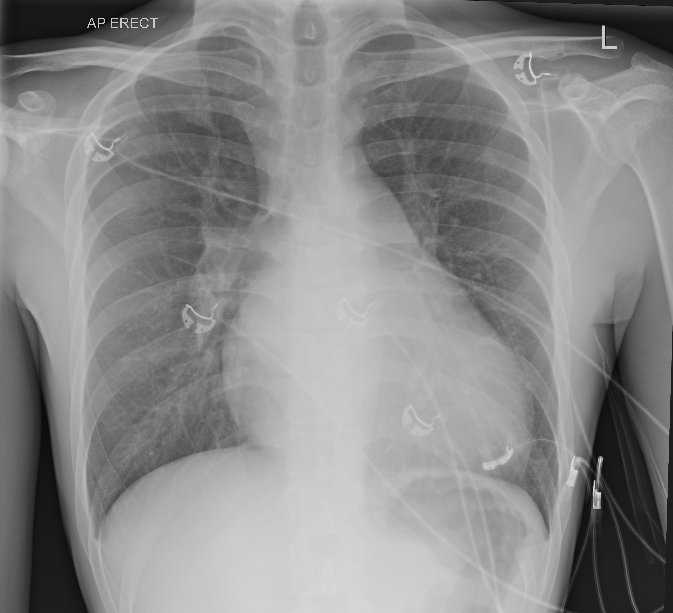

CXR is notable for an enlarged cardiac silhouette which is clearly abnormal in this young patient. Lung fields are largely clear, but there is some prominent upper lobe vasculature seen bilaterally. Costophrenic angles are clear.

The patient was only mildly symptomatic with this new diagnosis of atrial flutter/fibrillation.

There were no clear causes such as alcohol/drugs, or other features to suggest a metabolic/endocrine cause.

However, a new diagnosis of Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter in a young patient always requires consideration of underlying cardiac pathology. Enter….POCUS as a game-changer

Cardiac POCUS:

Here is the patients Parasternal Long-Axis view. We have talked previously about how powerful the PLAX is, and this single view essentially gives us the diagnosis and all the information we need about this patient.

Review the image thinking about focussing on the key areas of PLAX:

Pericardium (& pleural effusions)

LV size/function

RV : Aortic Root : LA ratio

Aortic root and aortic valve (& descending aorta)

Mitral valve

Basic POCUS: the PLAX

Here is some spaced repetition on the key areas of this important view.

Pericardium: There is no pericardial effusion, and there is no visible pleural effusion either.

LV size/function: The LV size and wall thickness appear normal (this can be confirmed with formal measurements). In this view the anterior septum (top), and the posterior wall (bottom) are both working well so there is no regional wall motion abnormality. The heart rate is fast and the systolic function is low-normal, slightly Lower than would be expected in a young patient. EF was estimated at 50%.

RV:Ao:LA ratio: it is difficult to precisely see the RV at the top of the screen but it certainly looks larger than the aortic root. Similarly, the Left Atrium is definitely enlarged (relative to the aortic root) - it is nearly the same size as the ventricle. So there appears to be RV enlargement, and LA dilation.

Aortic root & valve: Aortic root looks normal (ascending aorta not well seen in this view) and the aortic valve appears normal. If you can see the aortic leaflets opening during systole on the PLAX then the likelihood of there being any significant aortic stenosis is minimal.

Mitral Valve: If you look at the two valve leaflets they are not symmetrical, nor are they meeting properly. There is a clear gap visible between the leaflet tips during systole. In fact, the anterior (top) leaflet is completely prolapsing posteriorly. Without even putting colour over the valve we can tell they will have severe mitral regurgitation.

Putting it all together:

This patient has a prolapsing anterior mitral valve leaflet, which is likely causing severe mitral regurgitation. Features of severe MR are a dilated left atrium (as noted), atrial arrythmia such as AF/flutter (which the patient has), and pulmonary oedema from pulmonary hypertension and progressive RV failure (as noted by XR findings and dilated RV).

lmportantly- in severe MR the Left Ventricle is usually hyperdynamic (EF >65%), to compensate for the regurgitant loss of forward flow. In this case a low-normal EF is concerning as it may well indicate an LV which is starting to fail and urgent intervention to correct the valve may be required.

Intermediate POCUS:

We suspect this patient to have severe MR. Next we need to:

prove our diagnosis with colour doppler

look for the cause if possible

measure the pulmonary pressures

Below are two clips of the mitral valve from a PLAX (top) and Apical 4C (bottom)

Severe Mitral Regurgitation - the “Eccentric Jet”

The top PLAX clip shows a large MR jet which is directed posteriorly into the posterior (bottom) wall of the LA. If you review the first clip this makes sense due to the prolapsing anterior leaflet causing a gap allows blood to flow posteriorly. Watch how the jet continues to wrap all the way around the left atrium. This is called an ‘eccentric’ jet which often signifies severe mitral regurgitation. The bottom clip shows the jet continuing around the lateral and posterior wall of the LA.

Severe MR is usually diagnosed by using a combination of qualitative and quantitative criteria. A flail valve is highly suggestive of Severe MR, as is a large central jet greater than 40-50% of the LA area. Eccentric jets can be misleading however, as they may not look as dramatic as a large central jet. As the energy from the jet is absorbed into the atrial wall the colour flow may be narrow. However, any jet that is wrapping around the atrial wall such as these is significant.

To get an idea of what ‘Eccentric Jets’ can look like, below is a clip from a different patient with Severe MR. Note the very narrow MR jet that hugs the wall of the LA. The jet is narrow but continues all around the wall, signifying Severe MR.

Severe Mitral Regurgitation - Assessing Right Heart

In severe MR it is important to assess for RV failure. The LV will usually be hyperdynamic, but the increased pulmonary pressures cause RV afterload and can lead to RV failure.

The top clip is the Apical 4-Chamber. Whilst not a true “RV focussed view” (this would be obtained by moving slightly more laterally) we can see the RV is dilated. It is around the same size as the LV which is abnormal.

In this view you can also see the prolapsing anterior mitral valve leaflet which is causing the severe MR. Prolapse is defined by movement of the valves below an imaginary line drawn through the valve annulus (into the atrium in this example). Compare the mitral valve leaflets with the tricuspid valve leaflets on the left to see the difference.

PSAX - the “D-Shaped Septum”

The bottom video is a PSAX view, here you can appreciate the flattening of the intraventricular septum (or “D-shaped septum”) which indicates elevated pulmonary pressures. If you look at the septum (which runs from 9 o’clock to 1 o’clock in this PSAX view) it flattens more during systole (when the LV is contracting).

A D-shaped septum usually indicates Right Ventricular strain of some sort. Septal flattening in systole such as this, usually indicates RV pressure overload (suggesting high RV, and thus pulmonary pressures e.g. PHN, PE). Septal flattening during diastole usually indicates RV volume overload, such as caused by an atrial septal defect or severe tricuspid regurgitation.

Both a D-shaped septum and an enlarged RV are 2D signs suggestive of raised pulmonary pressures.

Severe Mitral Regurgitation - Measuring Pulmonary Pressures

The RV systolic pressure is measured by using the maximum velocity of the Tricuspid Regurgitation jet. Review the previous case for more details on measuring pulmonary pressures. The still below shows the CW doppler trace of the TR. See in the top of the frame on the 2D image how the CW is placed through the most prominent TR signal from the A4C view. A good trace will show a parabolic curve.

TR VMax was 364cm/s which gives an RVSP of 58mmHg

(the formula is RVSP = 4 x (Vmax)^2 but the machine will calculate this for you)

The clip below shows IVC assessment. Here the IVC is plethoric with minimal collapse with respiration (or sniffing). The IVC diameter was greater than 2.1cm.

This gave an estimate of Right Atrial Pressure (RAP) of 12mmHg.

Overall Pulmonary Artery Systolic Pressure were therefore estimated at :

58 + 12 = 70mmHg —> Severe pulmonary hypertension.

Case Progress:

The disposition of this patient drastically changed with the use of POCUS in ED. They were admitted under cardiology to a centre with cardiothoracic capabilities.

They remained haemodynamically stable and were worked up for imminent valve replacement. Pathology was thought to a cordae rupture but the exact cause was unclear. He did not appear to have any features suggestive of infective endocarditis.

The key points were recognising severe MR due to a flail valve leaflet, and identifying potential decompensation with an LV which was not hyperdynamic as would be expected.

Approach to stabilisation prior to valve surgery:

This is a complex topic, but this patient required intervention to repair or replace his mitral valve. As a general rule preparation for such surgery will involve several aspects:

Haemodynamic Optimisation: this centres on volume optimisation to reduce preload (diuresis) and BP control with a focus on decreasing afterload and maintaining the lowest acceptable BP. ACE inhibitors are important in reducing blood pressure and fluid load.

In the setting of cardiogenic shock inotropes or mechanical supports such as an IABP may be required. Respiratory support may be required for pulmonary congestion.

Rate and rhythm control: medium term rhythm control may be preferred as atrial fibrillation can be poorly tolerated in these patients. Cautious reduction in heart rate may be required, but a slight tachcycardia is preferable to bradycardia. This is because higher heart rates have a shorter systole reducing regurgitant time

TOE is important to image the valve in detail for surgical planning

Coronary angiogram is performed in anyone over 40yrs, or if suspicion of IHD, to assess if concurrent CABG is required at the same time as valve surgery.

Dental ‘clearance’ with OPG as any active dental infection is a contra-indication to valve surgery due to the high risk of infection.

Right heart catheterisation this is the gold standard for pulmonary artery pressure measurements and is useful to assess the degree of Pulmonary Hypertension and RV function. Can be used to further optimise pulmonary pressures prior to surgery and RV function is a predictor of survival.

Carotid doppler to assess for carotid stensis which is a stroke risk whilst on cardiac bypass

Lung function tests to assess and optimise any pulmonary disease which may be contributing to elevated pulmonary pressures. Can also predict ability to wean from ventilation post-operatively.

Severe Mitral Regurgitation - a rapid summary

Causes:

Infective Endocarditis

Chordae rupture (myxomatous, rheumatic, idiopathic)

Papillary muscle rupture (clasically from infero-posterior MI due to the single blood supply of the posterior papillary muscle). As the muscle has chords to both leaflets this can cause catastrophic MR and rapid cardiovascular collapse.

Chest trauma

Non-valvular causes such as LVOTO

Features:

Clinical: Atrial arrythmias, dyspnoea, pulmonary oedema, systolic murmur, tachycardia

Echo: flail leaflet, large colour MR jet or ‘eccentric’ jet, LA dilation, raised pulmonary pressures, hyperdynamic LV, pericardial effusion.

Management Principles in the ED:

Expect LV function to be hyperdynamic, if not this is concerning for impending LV failure.

Tolerate tachycardia as this is required to maintain forward cardiac output.

Respiratory support for pulmonary oedema (e.g. High-flow nasal prongs or NIV)

Target the lowest acceptable blood pressure to reduce afterload

Arterial Vasodilation to reduce afterload (e.g. GTN or Clevidipine)

Venous dilation to reduce RV preload in pulmonary congestion (e.g. GTN)

In frank cardiogenic shock the patient may need inotropic/vasopressor support and/or mechanical supports such as IABP or ECMO

Avoid atrial arrhythmia in unstable patients as this is often poorly tolerated. Treat AF with rapid ventricular response (AF w/ RVR) aggressively aiming for a high-normal HR (90-120). Avoid beta-blockers but consider amiodarone, digoxin, or DCCV.

Early cardiology and cardiothoracics surgical consultation for definitive management.