Cardiology Case #18

Primary Author: Dr Alastair Robertson; Co-Authors: Dr Hywel James and David Law

Background:

A 65 year-old female presented to ED with 1 day of intermittent left sided chest pain, and left arm pain.

She had a background of hypertension, but otherwise well. Of note on the history was significant recent social stressors.

Her observations were RR 18, Sats 96% on air, BP 180/90, afebrile.

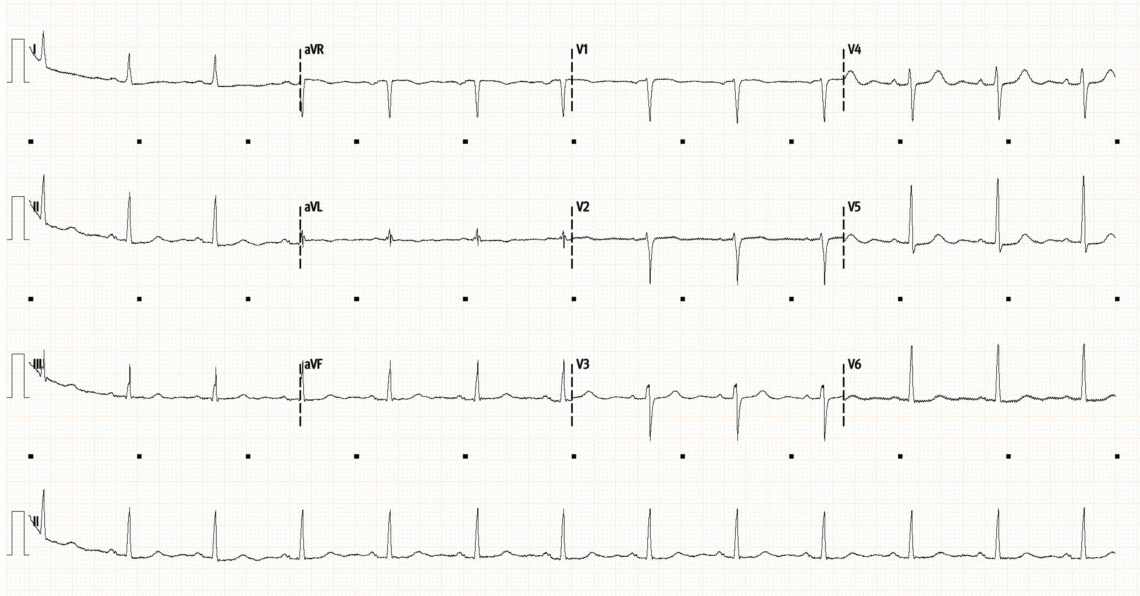

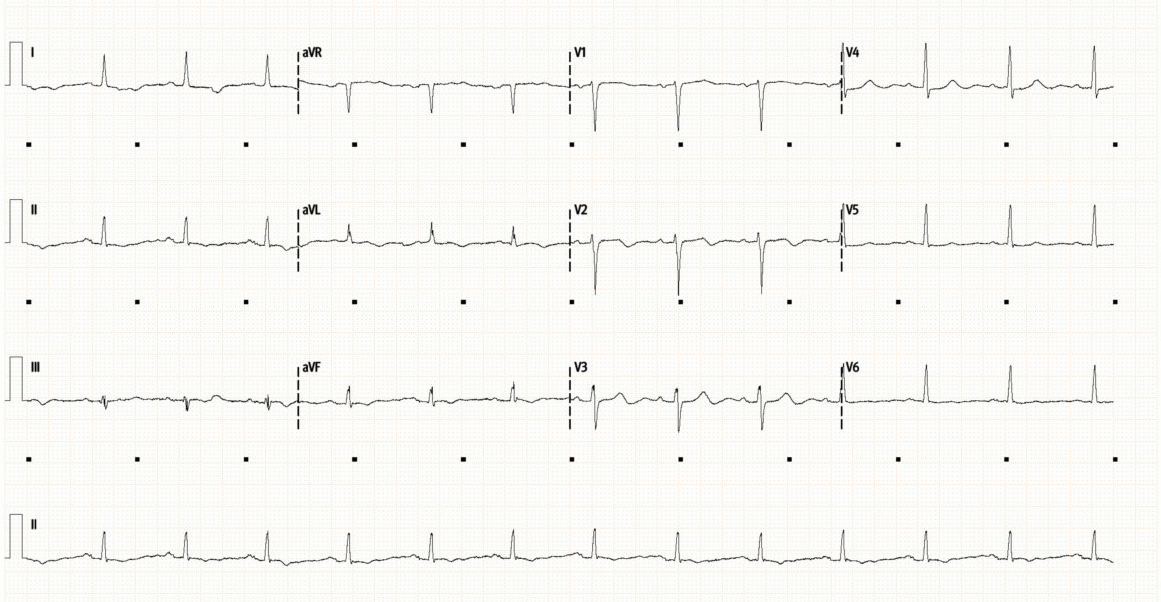

Below is her initial ECG (top), followed by repeat ECG 12 hours later (bottom).

What do you think?

Initial ECG (above), and repeat ECG (below)

-

Initial ECG shows a sinus rhythm at 80/min with normal axis and intervals. There are no significant ST or T-wave abnormalities. This is a very unremarkable ECG.

The repeat ECG shows some dynamic changes compared to prior. There is now subtle ST depression laterally (I, V4-6). There is new T-wave inversion in aVF, as well as new bi-phasic T-waves in V2/3. The T-waves laterally (V5/6) have also flattened compared to the initial ECG.

Dynamic ECG changes are always concerning for myocardial ischaemia. There is no clear single territory involved here but acute MI needs to be excluded.

The patient had been having intermittent arm pain on initial assessment. At the time of the repeat ECG her pain had resolved. One differential for biphasic T-waves which appear when the patient is pain free is suggest Wellen’s syndrome, and are the result of coronary reperfusion, though typically seen in a vascular distribution (most commonly anteriorly in V2/3 signifying critical LAD stenosis). However, there are other conditions which can also cause non-specific T-wave changes.

Initial troponin was 200ng/L, with repeat troponin uptrending at 800ng/L

She was managed as a NSTEMI with dual anti-platelets and enoxaparin.

Cardiac POCUS:

In the setting of Acute Coronary Syndrome POCUS can be incredibly useful. It allows assessment of:

Overall LV function: identify patients with significant impairment early to prioritise early reperfusion and help guide resuscitation with inotropes.

Regional wall motion abnormalities which can confirm the diagnosis of territorial ischaemia and would warrant earlier intervention/PCI.

May identify other causes of symptoms e.g. aortic dissection, pericardial effusion, valvular pathology, myocarditis, and cardiomyopathies (including stress induced - )

Below is a Parasternal Long-axis (PLAX - top), and then Parasternal Short-Axis views (PSAX) of the LV mid-cavity (middle) and then LV apex (bottom).

What do you think of the LV function?

Basic POCUS: the PLAX

The PLAX is a core image in echo.

Here we can see that the LV size looks normal, there is no pericardial effusion, and the RV:Aorta:LA ratio is approximately 1:1:1 which is normal.

What about the LV function? Well we need to look at both anterior and posterior LV walls, at the base and mid-cavity. The apex is not usually seen on a PLAX, however can be assess using low PLAX, PSAX and A2C, A4C and Apical LAX

First we can see here that that LV base is working well, the proximal anterior septum, and the proximal posterior segment are both working well, in fact they are hyperdynamic.

Now we look at the mid-cavity - here there is hypokinesis of both anterior and posterior walls with very little contraction.

As we have eluded to we cannot see the apex in a PLAX, but we can with the PSAX. Here the middle clip (LV mid-cavity) shows global poor contractility. In contrast the apex (bottom clip) appears to be working well with normal or even hyperdynamic activity.

This LV shows moderate segmental systolic impairment which appears to be involving the LV mid-cavity.

EF was measured at 40%.

Remember ischaemic cardiomyopathy typically shows segmental impairment matching the vascular territories, whilst takotsubo for example typically has a hyperdynamic base with apical ‘ballooning’ or hypokinesis.

So what is going on with this patient?

Intermediate POCUS:

The apical views are important to more accurately assess the vascular territories.

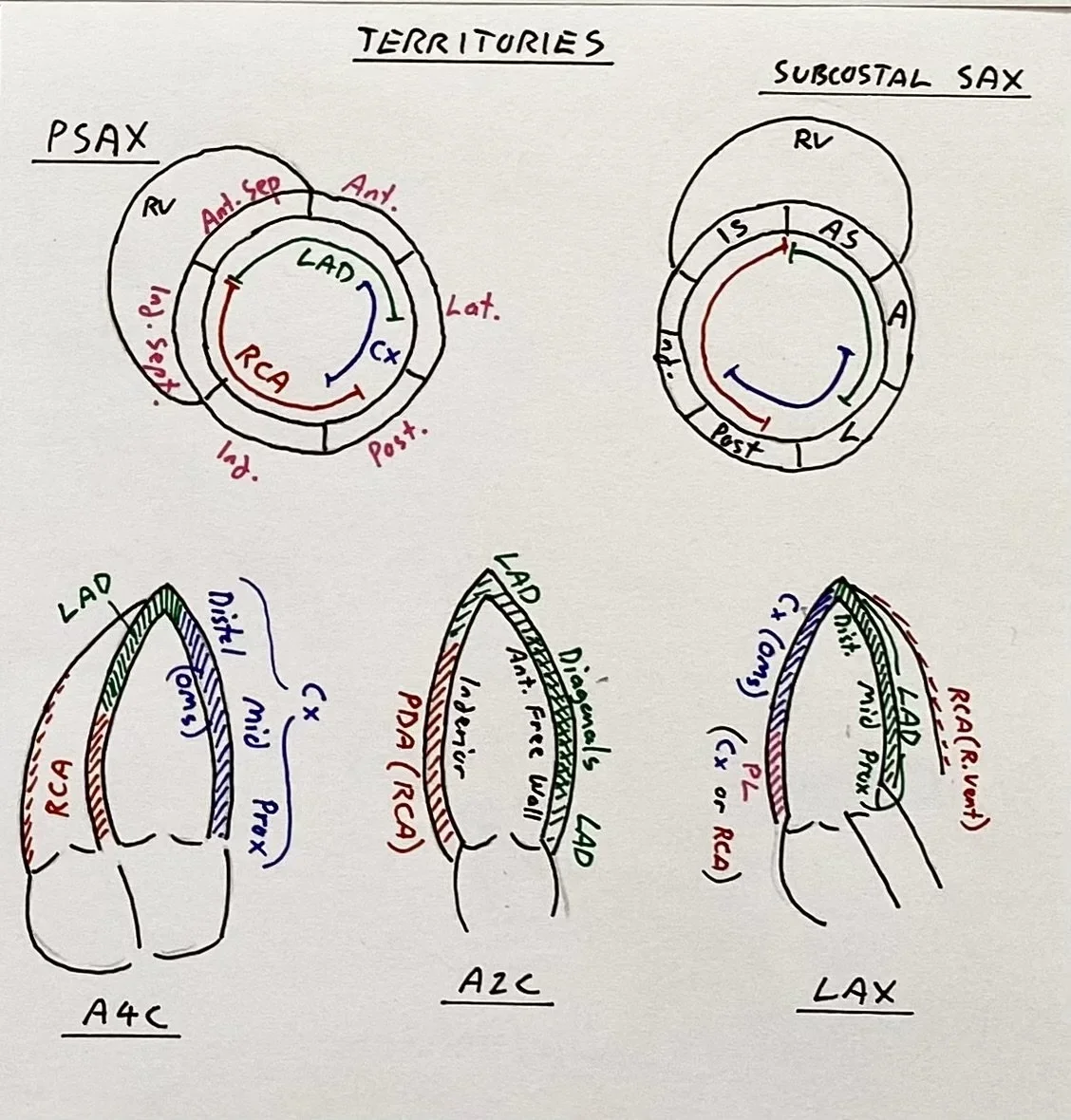

Review the clips below and the reminder of the vascular territories below.

POCUS interpretation:

Apical 4-Chamber:

This again shows that the mid-cavity is akinetic: both the lateral wall (LCx territory) as well as the septum (RCA or LAD territory)

Apex is very active, as is the LV base (both lateral wall, and basal septum)

Apical 2-Chamber:

The apex is active with good contractility (LAD territory)

The LV base is active both the inferior wall (left of screen - RCA territory), and the anterior free wall (right of screen - LAD/diagonals).

The mid-cavity of hypokinetic

Apical Long Axis:

This is the same view as a PLAX, but with better visualisation of the apex.

Again we see a hyperdynamic LV base (posterior wall LCx or RCA) as well as proximal septum (L main/LAD)

The apex is also hyperdynamic (LAD territory)

The mid-cavity is hypokinetic both anteriorly and posteriorly.

The apical views show extensive mid-cavity hypokinesis which does not map to a particular vascular territory. Apical function is preserved, as is LV basal function.

This is not typical of ischaemic cardiomyopathy due to vascular occlusion, but nor does it fit a typical takotsubo pattern (which usually has apical hypokinesis with a hyperdynamic LV).

Case Progress:

Troponin peaked at 1500ng/L

She had an angiogram the next morning which showed only mild non-obstructive coronary disease.

The final diagnosis was likely mid-cavity Takotsubo syndrome.

She was symptomatically improved, and was successfully discharged home on aspirin, beta-blocker, and statin with cardiology follow up and repeat echocardiogram.

FOCUS on Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy:

Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy (TTC), often referred to as ‘Stress-Induced Cardiomyopathy’ or “Broken Heart Syndrome” is an important differential for ED patients with suspected ACS. It is characterized by transient systolic dysfunction that extends beyond a single vascular territory, usually triggered by intense emotion or stress.

TTC accounts for about 2% of all patients presenting with suspected ACS, but the incidence is much higher in post-menopausal women (7-10% of suspected ACS presentations).

Trigger is thought to be a catecholamine surge which can be due to:

emotional stresses e.g. grief, interpersonal conflict, or even ‘happy’ triggers

physical stresses e.g. acute illness, pneumonia, stroke, seizure

iatrogenic e.g. adrenaline administration in anaphylaxis or dobutamine stress tests.

Presenting Features:

Presentation can be variable but the so-called ‘classic’ findings are:

Chest pain, SOB, pulmonary oedema, often with a history of emotional stress

Anterior ECG changes with ST elevation and/or deep T-wave inversion in V2-V5

Elevated troponin

On echo Classic TTC shows “apical ballooning” with akinesis of the LV apex and mid-segments, with compensatory hyperkinesis of the LV base which is less affected.

On angiogram the shape of the LV resembles a Japanese clay octopus trap, called a Takotsubo

Specific Echo Findings:

‘Classical’ Takotsubo (82% of TTC cases) - Apical ballooning/hypokinesis extending beyond a single vascular territory with basal hyperkinesis

RV involvement in about a third of cases (Bi-ventricular Takotsubo) with RV apical hypokinesis, and basal hyperkinesis

Variations of the Takotsubo syndrome exist with:

Mid-cavity Takotsubo (around 14% of TTC) - hypokinesis confined to the mid-cavity with hyperdynamic apex and base

Reverse or Basal/Inverted Takotsubo (around 2% of TTC) - hypokinesis of the LV base, but preserved mid/apical function. There have been case reports of this variant in certain overdoses e.g. Venlafaxine.

Focal Takotsubo (around 1-2%) - hypokinesis localised to a discrete area, often the anterolateral wall which may be indistinguishable from ACS without angiography.

Diagnosis and Differentials

In ED, Takotsubo is a diagnosis of exclusion and ACS (in particular anterior STEMI) is the most crucial must-not miss diagnosis. Diagnosis of TTC should definitively be made only be after coronary angiography.

Other differentials are:

Myocarditis: typically presents with more global LV impairment often in younger patients

Phaechromocytoma: can cause a catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy almost identical to TTC

Sympathomimetic toxicity: e.g. cocaine, stimulants

Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD): also more prevalent in female patients

Management of Takotsubo and its Complications in ED

LV impairment will usually resolve spontaneously, with most patients recovering normal cardiac function within 4-8 weeks.

Complications in the acute phase can be severe and in-hospital mortality is approximately 5% (which is at least similar to acute coronary syndromes). Mortality is highest in those with physical triggers (e.g. concurrent illness), males, and the elderly.

Complications include:

Pulmonary Oedema

due to poor LV function and raised LA pressures causing pulmonary congestion

management is with respiratory support (e.g. NIV), diuresis, and afterload reduction (e.g. GTN) to improve LV function.

LV Outflow Tract Obstruction (LVOTO)

One of the most feared complications of TTC.

Review the more detailed approach to management below.

Cardiogenic Shock

From poor LV function

General management principles include volume optimisation, afterload reduction if feasible, and potentially using inotropes to improve LV contractility

The big caveat in Takotsubo however, is that if LVOTO is present, extreme caution needs to be applied, as the management principles above may worsen cardiogenic shock.

Arrythmias

Occur in about 5-10% of cases

AF, VT, and even VF may occur.

Mechanism can be LV impairment, ongoing ischaemia or LA dilation from functional MR.

Importantly, QT prolongation is common in TTC which can precipitate arrythmias e.g. Torsades de Pointes.

LV Thrombus

Apical stasis can cause LV thrombus which can cause embolic complications.

Management is anticoagulation if present. Consider anticoagulation if LV impairment is severe (EF <30%) in line with other cardiomyopathies.

LV Outflow Tract Obstruction (LVOTO)

The hyperdynamic basal segments in Classical Takotsubo can cause obstruction of the LVOT, essentially causing an obstructive, rather than cardiogenic, shock.

The mechanism is that the hyper-active anterior basal septum narrows the outflow tract. With the increased blood flow due to the narrowed tract, the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve is sucked upwards due to the Venturi effect.

This Systolic Anterior Motion (SAM) of the mitral valve leaflet causes systolic obstruction of the outflow tract and is a key feature to look for on echo if LVOTO is suspected.

As the SAM displaces the anterior mitral leaflet from its usual position during systole this results in an incompetent valve. This causes severe MR due to the LV pumping against an obstructed outflow, with a now regurgitant mitral valve.

Rapid haemodynamic collapse can occur due to this obstructive shock.

Management Principles of LVOTO:

The approach to LVOTO managment is counter-intuitive, as measures that one would usually employ to improve LV function such as inotropes or afterload reduction can worsen the problem precipitating cardiac arrest.

1) Fluid Resuscitation (preload) - controlled fluid boluses (e.g. 250-500ml) are used to increase end-diastolic volume and help splint open the LVOT, keeping the mitral valve leaflet away from the septum. The goal is to open up the LVOT, at the potential expense of some LV dilation even with impaired LV function.

2) Beta-blockers - are key to managing true LVOTO as they will slow the heart rate (increasing diastolic filling/preload and reduce basal hyper-contractility). Avoid inotropes such as Adrenaline as this can just worsen LVOTO. This is counter-intuitive and one needs to be sure that the problem is obstructive (LVOTO) rather than cardiogenic (poor LV function) and the management approaches are opposite.

If using beta-blockers an Esmolol infusion is a good choice, being titratable and ultra-short acting. Low dose metoprolol could also be considered.

3) Vasopressors - if further support is needed to maintain an acceptable MAP consider use of pure vasopressors such as Metaraminol or Phenylephrine to increase systemic vascular resistance. This can help support the blood pressure and increasing afterload which may help splint open the LVOT. Avoid agents with beta-agonism such as Adrenaline or Noradrenaline if possible.

4) Mechanical Supports - for refractory shock. Whilst an Intra-aortic balloon pump or Impella can be useful in severe cardiogenic shock, they both reduce afterload, and are not the best treatment for obstructive shock caused by LVOTO.

VA ECMO is the preferred rescue modality, as it gives retrograde afterload via the arterial cannula which can help keep the the LVOT open. It will decrease preload via venous drainage, but is probably the best approach to refractory LVOTO, allowing time to initiate beta-blockade to resolve the problem.

Finally:

Other conditions where LVOT Obstruction might be seen:

Hypertrophy: HCM/HOCM, hypertensive heart disease, sigmoid septum (elderly)

Acute pathology: large anterior or apical MI can cause a takotsubo-like compensatory basal hyper-kinesis with resultant LVOTO.

Post-surgical: after Mitral Valve repair or TAVI where the LV geometry is altered

Hypovolaemic or Distributive Shock with a hyper-dynamic LV e.g. dehydration, anaphylaxis, or withdrawal states with significant dehydration.

Drug induced: - high dose Adrenaline or Dobutamine, overdose of sympathomimetics or stimulants (theophylline, cocaine, cathinones)